How to Stimulate the Vagus Nerve with Breathing Exercises

How to Hack Your Breathing to Optimize Physical and Mental Recovery and Prevent Overtraining

If you’re like most people, you don’t have an intimate anatomical knowledge of your nervous system, or the anatomy of your vagus nerve. But you’re probably familiar with your “fight or flight” response, the sympathetic nervous system, or SNS. The sweaty palmed, adrenaline-charged, bladder gripping, gut twisting physical stress reaction.

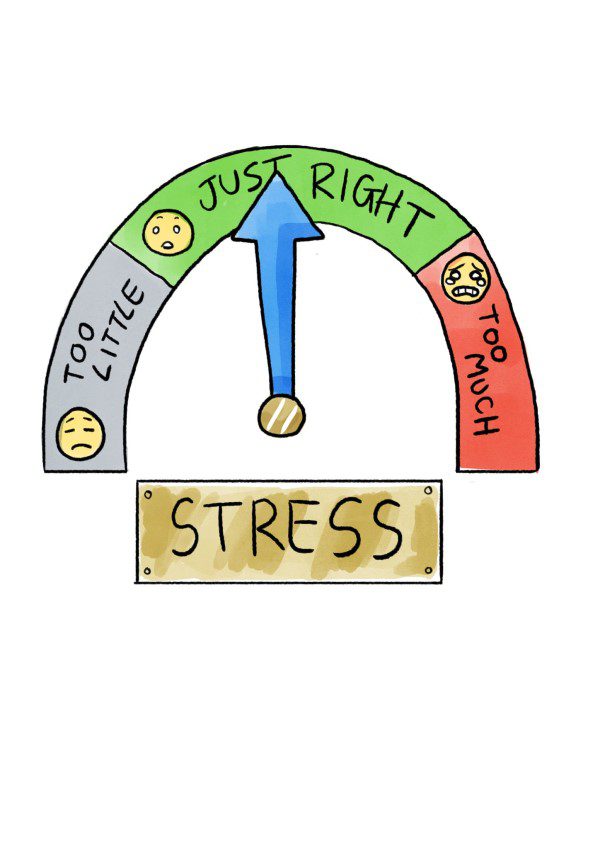

The SNS is the evolutionary mechanism that primes you to fight, run or freeze when danger strikes. It has its uses. But when it activates too often — or all the time — you can end up chronically stressed. And stress is not “just” in the mind. It floods the body with hormones, shuts off important brain functions, contributes to inflammation. It’s a risk factor in 75 to 90% of human diseases.

Your stress response is part of your autonomic nervous system (ANS). This is the system in your body that takes care of automatic functions. Things like breathing rhythm, heart rate, digestion, and blood pressure. The body’s systems need to stay balanced to work. If your blood pH or blood pressure increase, the autonomic nervous system kicks in to rebalance things. To maintain this stable environment, the ANS needs two branches. One to up-regulate, and one to down-regulate.

The sympathetic nervous system or SNS up-regulates your autonomic nervous system. The branch that balances it is called the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). It’s the “rest and digest” part that counters the “fight, flight and freeze.”

Constant interplay between the SNS and PNS keeps the body in homeostasis or equilibrium. You need homeostasis to survive. In fact, stress can be simply defined as anything that disrupts homeostasis.

Wait. What about the vagus nerve?

What is the Vagus Nerve?

What’s the Anatomy of the Vagus Nerve?

The vagus nerve is the tenth cranial nerve. It is also the longest. It travels right down to the colon, connecting with all the major organs along the way. Most of its nerve fibers are the body-to-brain type. They feed information about what’s going on in the body back to the brain.

The reason we spent some time learning about the ANS is that the vagus nerve is the main “driver” of the PNS. It’s the vagus nerve that controls your “rest and digest” functions.

Now here’s the juice.

You can stimulate the vagus nerve “on purpose,” whenever you want to. And you can measure your results using something called heart rate variability (HRV). And… the more you do this, the better your health will be.

First, let’s find out why this is useful. Then we’ll look at how it’s possible. Before you go scratching around under your armpit looking for a button, here’s a clue. It’s something to do with the breath.

What is Vagal Tone?

When the “fight or flight” response is stuck in “always on” mode, sympathetic activation is high. Remember the ANS has two branches. Imagine the SNS and PNS as two ends of a seesaw. If sympathetic activation is high, parasympathetic tone will be low. You will also be super stressed and (probably) not very well.

Good vagal tone means your PNS is working, and your body is in balance. Low vagal tone and stress are closely linked. Remember the statistic about stress and disease? Poor vagal tone is symptomatic of poor physical and mental health. When your vagal tone is low, you’re off balance.

How Do I Measure my Vagal Tone?

Vagal tone can be measured using heart rate variability (HRV). Did you know, the heart does not beat like a metronome? It constantly slows and speeds up as it adjusts to things happening inside and outside the body. These constant fluctuations in heart rate are called HRV. HRV is measured as the time and frequency between heart beats. The more variability there is between these beats, the more adaptable your body is. Your systems can change gear more easily, respond to stress and maintain equilibrium.

When vagal tone is good, your heart rate also changes as you breathe. It speeds up during inhalation and slows during exhalation. This is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). The heart in synchronicity with the breath.

Scientists have reported a positive feedback loop between high vagal tone and wellbeing. This indicates that good vagal tone supports positive emotions and good physical health. The more you improve your vagal tone, the better your physical and mental health will be.

- Heart disease

- Stroke

- Cancer

- High blood pressure

- Alzheimer’s

- Diabetes

- Intentional self-harm

- Depression, anxiety, panic disorder and PTSD

- Erectile dysfunction in men and sexual dysfunction in women

Low HRV is associated with early mortality. It can be passed on from mother to baby. It can also occur in successful athletes who overtrain and sleep badly. And in otherwise healthy people who have dysfunctional breathing.

Vagal tone in the heart is also closely linked to both breath and emotions, affecting interpersonal qualities such as empathy, emotional regulation and attachment.

HRV can be used to measure vagal tone. It is very easy to track. And it is very possible to improve your HRV. This is important because it means you can improve your vagal tone. Which means you can improve your health. Which is kind of empowering.

Also, when vagal tone increases, it improves long-term. Which means that working to optimize your HRV will have an ongoing positive impact. You’ll become more resilient, physically, and mentally.

It’s also a valuable measure for doctors because it allows them to quantify stress and susceptibility to stress-related illness based on physical parameters. Stress can then be defined in terms of the direct effect it has on organs like the heart, rather than as a purely mental or emotional issue.

In other words, it’s not all in your head.

Breathing for Relaxation

During stress, breathing tends to speed up. We’ve already seen the connection between stress and disease. What’s more, very fast breathing is the #1 predictor of heart attacks in hospital patients.

Now let’s look at a few benefits of slow breathing:

- Slow, nose breathing engages the diaphragm. Which is connected to the vagus nerve.

- The diaphragm is also connected to the heart. So deep breathing with bigger diaphragm movements actually “massages” the heart from within.

- Slow breathing calms the nervous system because slower exhalations activate the PNS.

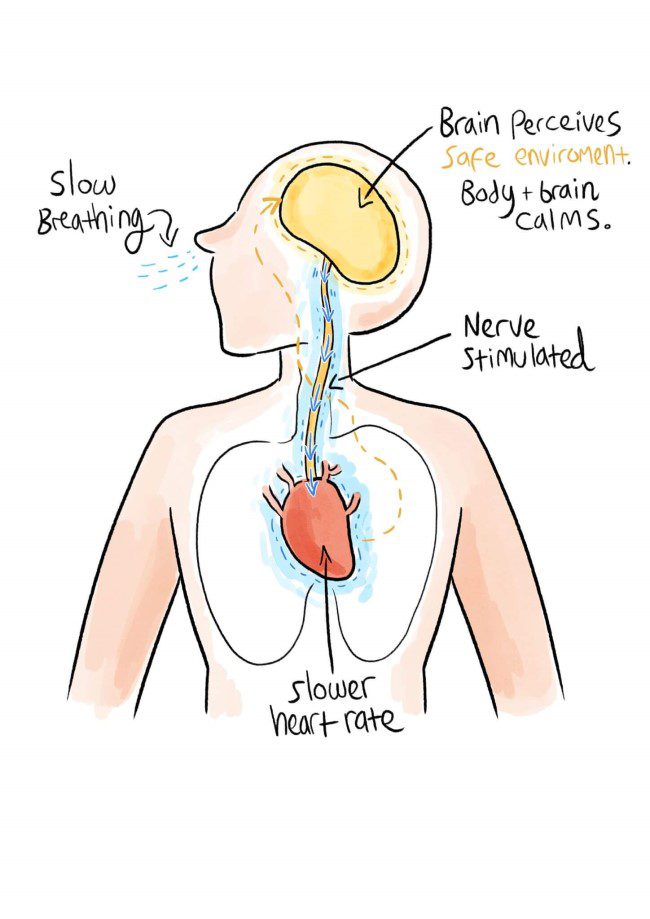

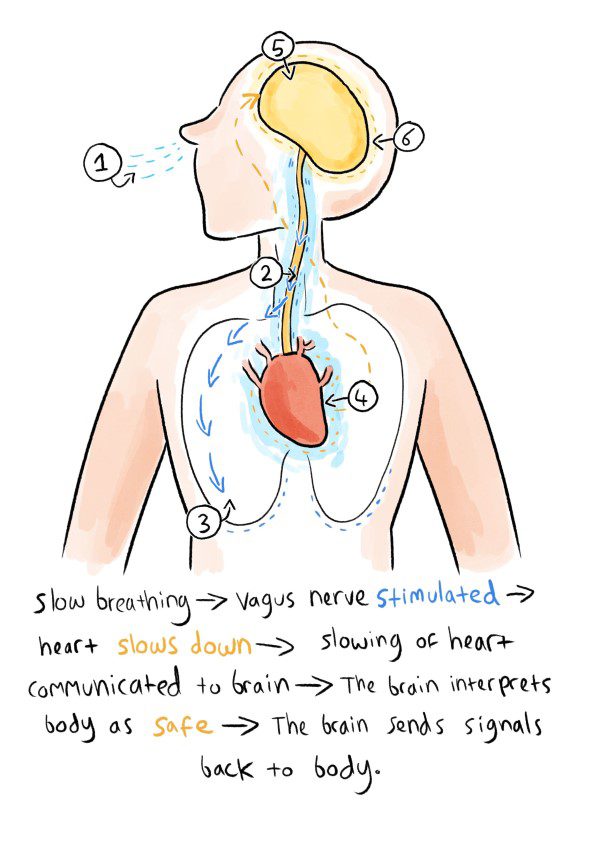

Remember, the PNS is the body’s relaxation response. It is controlled by the vagus nerve. When you breathe out, the vagus nerve releases a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. Neurotransmitters are chemical “messengers.” Acetylcholine (ACh) causes blood vessels to dilate, and it slows the heart rate. It is also found in the brain, where it is important for memory and cognition.

Here’s the thing… The vagus nerve is only active in this way during exhalation. Which is why many yogic slow breathing practices emphasize the exhalation. It is during exhalation that the vagus nerve releases its calming messenger, acetylcholine. It is by breathing out that we can build vagal tone.

During slow breathing, the exhalation is naturally longer. At the same time, CO2 builds up in the blood. Carbon dioxide is also known to make the vagus nerve more sensitive. It slows the pulse and improves the blood-filling of the heart. So increased CO2 and exhalation are both important.

All this is contrary to what many people believe about breathing. The good stuff happens during the slow exhalation. Not when we “take a deep breath.”

Think of it this way. It can feel almost impossible to control the constant stress we experience. Often, this underlying stress makes challenging events harder to deal with. Sleep suffers and stress piles up. You begin to get sick. But what if there was a way to rebalance your system? To activate your relaxation response. To increase vagal tone?

There is.

You can learn to stimulate your vagus nerve.

How Do I Stimulate My Vagus Nerve?

So, what stimulates the vagus nerve?

- Cold

- Slow diaphragm breathing

- Vagus nerve massage

- Meditation

- Singing, laughing and humming

- Sex…

Cold Stimulates the Vagus Nerve

The breathwork guru, Wim Hof suggests several ways to stimulate the vagus nerve. Wim Hof’s breathing technique involves deliberate hyperventilation and exposure to cold. He says that:

“Exposing your body to acute cold conditions, such as taking a cold shower or splashing cold water on your face, increases stimulation of the vagus nerve. While your body adjusts to the cold, sympathetic activity declines, while parasympathetic activity increases.”

It’s true that submerging the face in cold water increases PNS activity. The vagus nerve is responsible for many movements of the mouth including chewing and swallowing. According to behavioral neuroscientist, Dr. Stephen Porges, we can change our mental state just by using the muscles in our face.

Porges has published detailed research into the social functions of the vagus nerve. He says our interactions with others can increase vagal tone and calm the SNS. Think about the last time you were at a party where you didn’t know anyone. As soon as you smiled at someone, you felt better, right? That’s your vagus nerve. Scientists have also shown babies with more expressive faces have higher vagal tone. And the cosmetic treatment, Botox, which reduces signs of aging by minimizing facial expression, works by preventing the release of acetylcholine.

Splashing cold water on the back of the neck can also activate the vagus nerve. One research paper suggests wetting the face and neck with cold water after exercise. Scientists think this may balance the SNS and relieve stress on the heart. But research also shows that full body cold water immersion can be dangerous. It can activate the SNS and PNS simultaneously. And that can cause potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmia. This was demonstrated recently in the tragic case of a UK radiographer who died from cold water immersion syndrome while attempting a sea swim.

Breathing Relaxation Techniques for Vagus Nerve Stimulation

We know the vagus nerve is closely connected with the breath. It squirts relaxing acetylcholine into your body when you breathe out. Good vagal tone can be measured with HRV, which is connected with RSA – the heart and breath in sync. And you can improve HRV with slow diaphragm breathing.

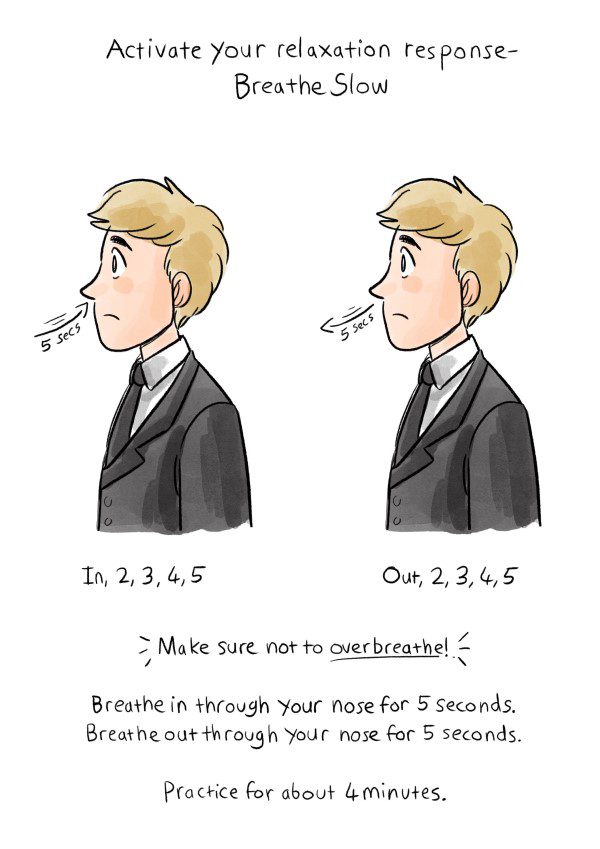

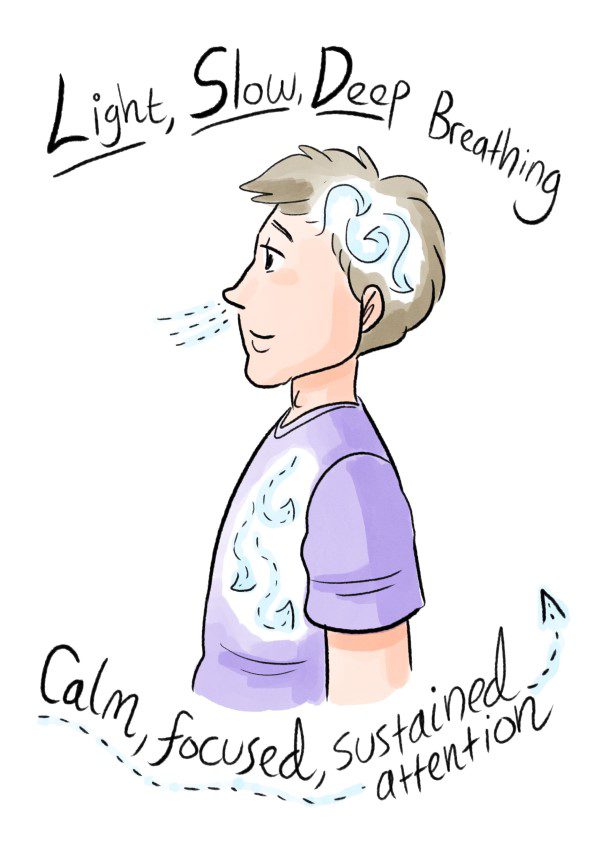

A wide variety of research studies show that there is an optimum breathing rate. When you practice slow breathing, it optimizes HRV, RSA, blood gas exchange, blood pressure and all sorts of vital systems in the body. At a breathing rate of between 4.5 and 6.5 breaths per minute, vagal tone improves. Most research settles on 6 breaths a minute as ideal [1]. One paper narrows it down to 5.5 breaths, with an equal ratio of exhalation and inhalation. Others say that longer exhalations are better.

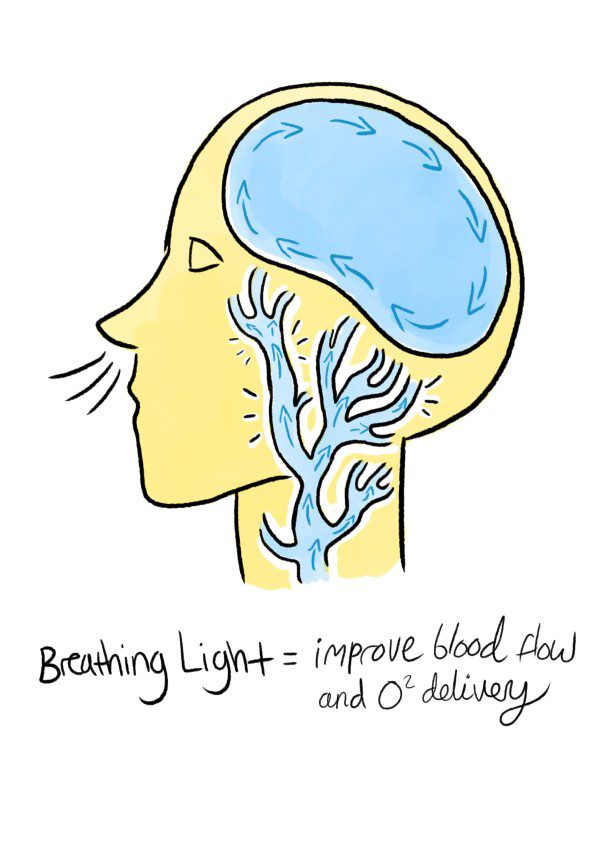

How does this work? Well, if you breathe slower, you spend more time exhaling. So, you spend more time in PNS dominance. You secrete more acetylcholine. Your heart spends longer in its slow phase, so it has more time to fill with blood. You activate the diaphragm, which is innervated by the vagus nerve. Inhaled air gets deeper into your lungs, so there’s more time for the lungs to extract oxygen. Carbon dioxide increases in your blood. CO2 acts to dilate the blood vessels. More CO2 means better circulation and better blood pressure. Blood flow to your brain improves and this has a calming effect. You breathe in more nitric oxide which opens the blood vessels in the lungs. Conversely, low CO2 is known to trigger panic attacks.

You can read about the research into 6 breaths a minute in much more detail in Patrick McKeown’s book, The Breathing Cure.

Meditation is another way to bring the body and mind into a calm state. Many forms of meditation involve conscious breathing. Or at least, bringing attention to the breath. Scientists discovered that during transcendental meditation, breathing can slow almost to a stop. When you bring your body to a calm state, the vagus nerve feeds this calm back to the brain. The SNS deactivates and vagal tone increases.

Singing, humming, and gargling can all activate the vagus nerve via the muscles in the back of the throat. Humming also creates powerful vibrations in the nasal cavity. And this boosts production of nasal nitric oxide (NO). In one study, significantly more NO was found in the nose after strong humming. Scientists have also found a connection between vagal tone and chanting. The mantra om-mani-padme-hum and the Latin rosary prayer both reduce the breathing rate to 6 breaths per minute.

What’s the Link Between Sex and Vagus Nerve Massage?

In women, the vagus nerve directly connects to the cervix and uterus, which means penetrative sex massages the nerve. The vagus nerve innervates the voice box and throat too. Scientists exploring involuntary vocal noises during sex linked the sounds with hyperventilation. And Suzie Heumann, found of Tantra.com suggests that slow, deep breathing may connect with the vagus nerve to enhance female orgasm.

How Do I Increase Vagal Tone?

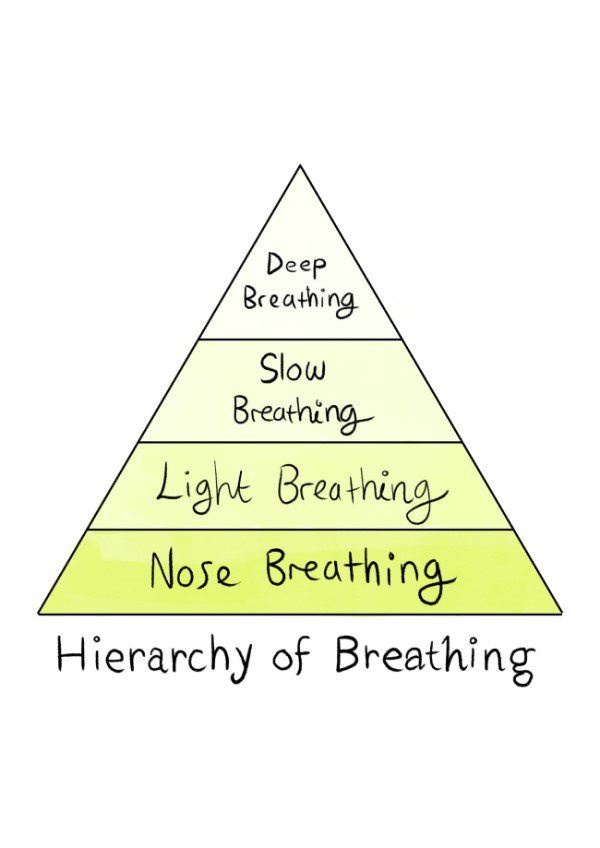

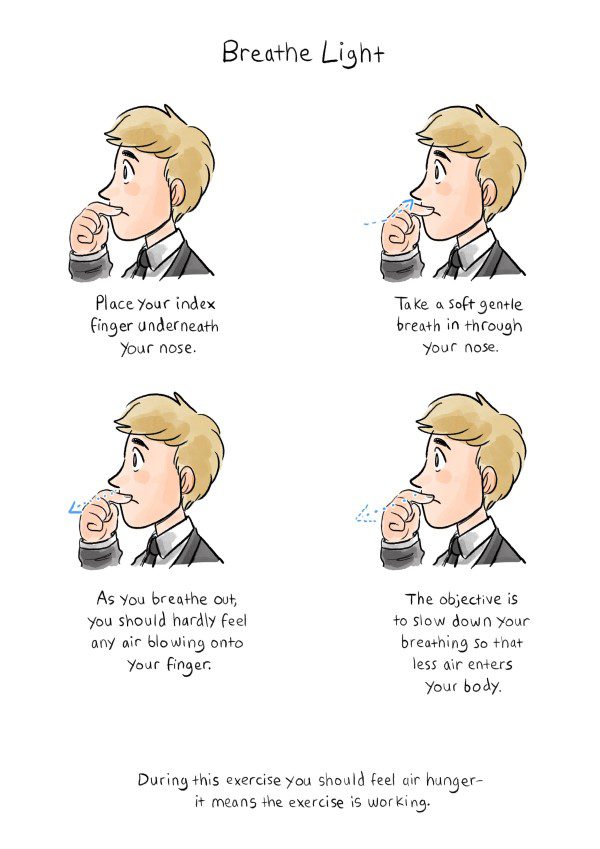

You can influence your vagus nerve using the OA™ exercises. These focus on:

- Nasal breathing,

- Light breathing,

- Deep breathing

- Slow breathing.

It’s important to get a quality HRV device. Look at products in the $300 range. The Lief Therapeutics wearable ECG, the Polar H10 Chest Strap with the Elite HRV app, BioStrap, Oura Ring, WHOOP Strap, and HeartMath Inner Balance™ or emWave2® are all reliable.

If possible, work with a breathing instructor to understand what changes in HRV mean for you. For instance, if your HRV is lower after intensive training, you may be at higher risk of injury the next day. If your HRV is consistently high, you may be experiencing overtraining syndrome. This information can be invaluable when it comes to adjusting your training load.

How to Stimulate the Vagus Nerve — What the Research Says

Now it’s time to answer some more specific questions about the vagus nerve, and how it impacts your health…

Q1. Who Discovered the Functions of the Vagus Nerve?

The chemical messenger released by the vagus nerve was identified in 1913 by an English chemist called Arthur Ewins and his colleague the pharmacologist and physiologist Sir Henry Hallett Dale.

Then in 1921, Otto Loewi found that activation of the vagus nerve triggered it to secrete a substance he called Vagusstuff. Vagusstuff, which turned out to be acetylcholine, caused the heart rate to slow, simulating relaxation or activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. This “relaxation on tap” is the physical and mental equivalent of having a reboot button.

Loewi and Dale were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1936 “for their discoveries relating to chemical transmission of nerve impulses.”

Q2. What is HRV Biofeedback and What is It Used For?

In the 1990s, a research psychologist and clinician called Paul Lehrer devised a technique called heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB). The main idea was to slow down the breath to get beat-by-beat heart rate data. This data (or feedback) allowed the patient to maximize RSA, synchronizing the heart rate and breathing pattern.

HRVB reduces stress in otherwise healthy people [2]. It can be used to improve athletic performance [3]. And it can be used to help conditions as wide-ranging as asthma, COPD, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, hypertension, cardiac rehabilitation, long-term muscle pain, anxiety, depression, PTSD and insomnia.

The improvements in gas exchange that come from HRVB training can also reduce symptoms of respiratory diseases, relieve stress induced hyperventilation, restore balance in the autonomic nervous system, and regulate inflammation [4].

Q3. Should My Exhalations Be Longer Than My Inhalations?

Traditions such as yoga teach slow, deep breathing techniques with an emphasis on longer exhalations. When you understand that the vagus nerve is stimulated during the exhalation, this makes perfect sense. In OA™ we often use a prolonged exhalation to down-regulate the nervous system

Countless trials have found that 6 breaths a minute is optimal for a whole catalogue of reasons. But these often compared wildly different breathing rates, like 13, 6 and 3 breaths a minute. One study examined rates within a much narrower range — 6 and 5.5 breaths a minute — and came up with more specific guidance.

Scientists also tested different inhalation to exhalation ratios – 5:5 (equal) and 4:6 (with a longer exhalation than inhalation). The expectation was that the longer exhalations would provide greater relaxation and a bigger increase in HRV.

But the results showed that a rate of 5.5 breaths per minute with an equal ratio of inhalation to exhalation (5:5) increased HRV most significantly. It also improved function in the blood pressure receptors and enhanced activation of the vagus nerve most effectively [5].

Q4. How Can I Use Breathing and HRV to Regulate My Blood Pressure?

The blood pressure receptors (baroreflex) control blood pressure by managing flow. When blood pressure increases, the baroreflex slows the heart. When blood pressure decreases, it causes the heart rate to increase, raising levels back to normal. This constant balancing is necessary to keep the blood pressure at a sustainable level. Like opening and closing a tap to regulate water flow. Not too high, not too low. Blood pressure doesn’t just react to stressful events and intensive exercise. It fluctuates constantly when you breathe, due to pressure changes in the chest.

When the breath-to-heart-rate-ratio is optimized in terms of blood gas exchange, the baroreflex is at its most efficient. To achieve this efficiency, you can use breathing to increase HRV via the vagus nerve. And if you use an HRV tracking device, you’ll be glad to know that HRVB can help strengthen your baroreflex [3].

The baroreflex is not just a control mechanism. Its functioning affects the ease with which blood vessels contract and dilate (vascular tone). Baroreflex sensitivity is linked to the body’s sensitivity to blood carbon dioxide too. The baroreceptors work most effectively when you have reduced sensitivity to CO2.

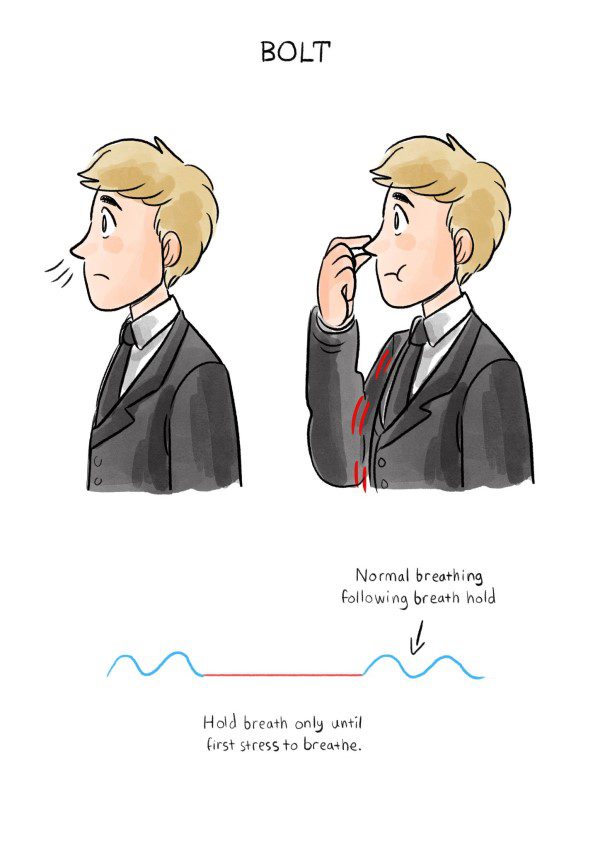

You can reduce your sensitivity to CO2 by increasing your BOLT score. A BOLT of more than 25 seconds indicates a functional baroreflex. Lower baroreflex sensitivity to CO2 produces a slower heart rate and better vagal tone.

The connection across all these systems is slow breathing at 6 breaths a minute. Slow breathing stimulates the baroreceptors to become more responsive to changes in blood pressure. It makes the heart rate more flexible and enlivened. It awakens the reactivity of the vagus nerve.

And it shifts the balance of the autonomic nervous system away from the stressed-out “fight or flight” mode, towards an open, relaxed, socially oriented outlook. Allowing you to thrive on a physical, mental, and social level.

Q5. I find Slow Breathing Difficult. Is That Normal?

Yes, it’s normal. Some people find slow breathing practice uncomfortable. If you have a bit of a perfectionist streak, you might even find it stressful to bring attention to the breath — in case you get it wrong!

There’s a physical reason it may feel difficult too. When you slow down your breath, the volume of air that reaches the air sacs in your lungs will increase. The amount of air per breath may well increase too. But overall, you are likely to breathe a lower volume of air per minute. This is likely to result in feelings of air hunger. Especially if your sensitivity to blood CO2 is high.

If you want to begin a practice of 5.5 or 6 breaths a minute, it’s a good idea to slow your breath a bit at a time. Start by breathing in for 3 seconds and out for 3 seconds. If that’s too tough, begin with 2 seconds. Anything that is slower than your normal breathing rate is a great start.

Q6. How Will I Know If I’ve Stimulated My Vagus Nerve?

When you practice the breathing exercises, it’s important to listen to your body. If you start to feel stressed, if your mouth becomes dry, or if your hands feel cold, you’re pushing too hard, and activating your stress response.

As you stimulate the vagus nerve, you may start to feel a little drowsy. You may also notice a slight increase in watery saliva in your mouth. Your hands will begin to feel a little warmer as blood vessels dilate and your circulation improves.

Throughout the day, bring your attention to your breath. Breathe nose, slow and low.

In a fast-paced, hectic world, where many things seem outside your control, slow breathing becomes an essential element of self-care.

The choice is yours. Stay stressed. Or take some time out today to slow down and tap into your vagus nerve, improving your experience, your resilience, and your long-term health.

Breathe in, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, out 2, 3, 4, 5, 6…

To learn more about the vagus nerve and HRV, check out our podcast with OA founder Patrick McKeown and our consultant, HRV specialist, Dr. Jay Wiles.

References:

- Russo, Marc A., Danielle M. Santarelli, and Dean O’Rourke. “The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human.” Breathe13, no. 4 (2017): 298-309.

- Vaschillo, Evgeny, Paul Lehrer, Naphtali Rishe, and Mikhail Konstantinov. “Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: a preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system.” Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback27, no. 1 (2002): 1-27.

- Lehrer, Paul M., and Richard Gevirtz. “Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work?.” Frontiers in psychology 5 (2014): 756.

- Lehrer, Paul, Maria Katsamanis Karavidas, Shou-En Lu, Susette M. Coyle, Leo O. Oikawa, Marie Macor, Steve E. Calvano, and Stephen F. Lowry. “Voluntarily produced increases in heart rate variability modulate autonomic effects of endotoxin induced systemic inflammation: an exploratory study.” Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback35, no. 4 (2010): 303-315.

- Lin, I. M., L. Y. Tai, and Sheng-Yu Fan. “Breathing at a rate of 5.5 breaths per minute with equal inhalation-to-exhalation ratio increases heart rate variability.” International Journal of Psychophysiology91, no. 3 (2014): 206-211.