Science / Functional Breathing Technique / Mouth Breathing: Face, Sleep, Effects

Mouth Breathing Face: How to Fix and Sleep Effects

Why Breathing Through an Open Mouth Is Bad News for Adults and Children, and How to Fix It

If you’ve read the other articles in our Science section, you will know by now that healthy, efficient breathing happens through the nose. But if your nose is blocked, or your tolerance to carbon dioxide is very low, it’s likely you habitually open your mouth to breathe. As many as 90% of us have a deviated nasal septum, where the cartilage between the nostrils is crooked. Children often experience swollen adenoids and tonsils that block the nasal airway.

A sedentary lifestyle, poor cardiovascular fitness, and misconceptions about breathing all play their part. But if you breathe through an open mouth, during exercise, in a protective face mask, when you sleep, or just by force of habit, you may be surprised by the damage your breathing can cause. If your child is a mouth breather, things are perhaps even more serious. Let’s look at the effects of mouth breathing and find out how to resolve it.

What Is Mouth Breathing?

Mouth breathing is a dysfunctional breathing pattern, related to stress and disease states. If you notice yourself breathing through your mouth almost all the time, or you’re a nighttime mouth breather, there are steps you can take to restore healthy breathing. While mouth breathing is “normal” if you have a heavy cold, or are exercising intensively, chronic mouth breathing indicates a problem. What’s more, whether mouth breathing is the cause or result of your symptoms, breathing re-education to restore nasal breathing will help you feel better and perform better. In children, it’s essential for healthy growth of the face, teeth, airways, and brain.

What Causes Mouth Breathing?

Mouth breathing can be caused by anything that puts your body, and your breathing, out of balance. Some of these mouth breathing causes may not be immediately obvious. Here are just a few reasons you may be breathing through your mouth:

- Asthma

- Allergies

- A deviated nasal septum or other physical nasal obstruction

- Chronic colds or airway infections

- Swollen or enlarged tonsils and/or adenoids

- Polyps in your sinuses

- A history of thumb or finger-sucking

- A history of childhood mouth breathing

- A small nose

- Birth abnormalities including cleft palate, tongue-tie, and lip-tie [1]

- Down syndrome

- Poor posture, especially if you sit in front of a computer all day or drive professionally

- Emotional stress, panic disorder and/or anxiety

- Extra resistance to breathing caused by your face mask

- Bottle feeding or overuse of a pacifier in infancy [2,3]

Habitual mouth breathing will itself cause mouth breathing. If you’re already a mouth breather, it’s likely your nose is too bunged up to breathe through it.

At night, mouth breathing can happen as you get older. Once you reach the age of 40, you’re 60% more likely to spend at least half the night breathing through an open mouth [4]. In postmenopausal women, the risk of sleep apnea increases by 200% compared with women who are still menstruating [5].

If you carry a bit of extra weight, fat on your tongue, neck and belly can cause mouth breathing during sleep. So can sleeping on your back, an overheated, stuffy room, drinking alcohol before bed, and eating late.

Is Mouth Breathing Bad?

You know we wouldn’t have devoted an entire article to the negative effects of mouth breathing if it were healthy. So, let’s just cut to the chase and begin to answer some questions. First off, if so many of us are doing it, why is mouth breathing bad?

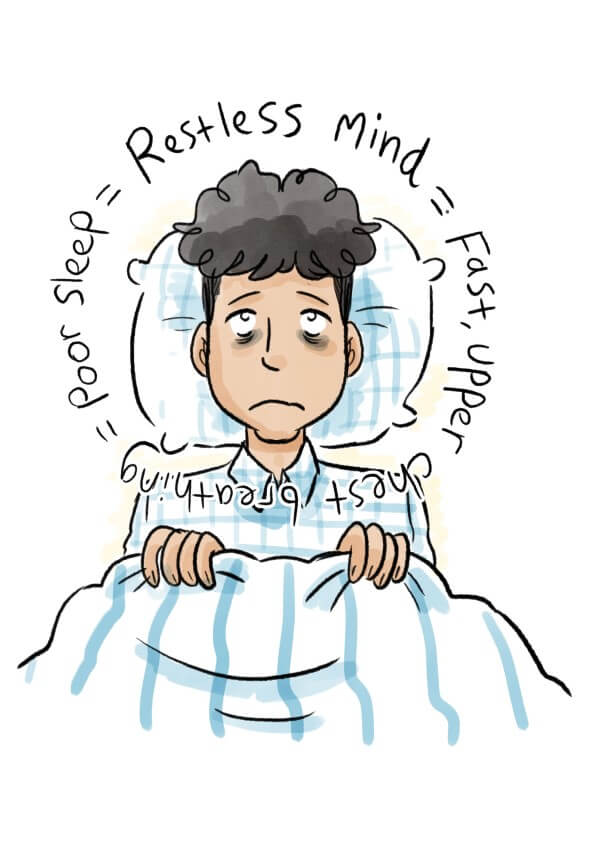

Mouth breathing is often fast, hard, audible and involves visible movement of the upper chest. Sometimes it’s punctuated by heavy sighs. You’d expect to see this type of breathing in someone who is very stressed or breathless.

But for habitual mouth breathers, the negative side effects of mouth breathing become chronic, due, in part to over-breathing or hyperventilation. Hyperventilation is defined as breathing too much air, reducing levels of blood carbon dioxide below normal. Long term, mouth breathing has a serious negative impact on health and longevity, and even on the way your face looks.

Mouth Breathing Symptoms — Things to Look Out For

“Back in 1909, an article, “Habitual Mouth-Breathing and Consequent Malocclusion of the Teeth,” was published in The Dental Cosmos. In it, DeLong described how mouth-breathing can cause the sleeper to wake with a dry mouth and throat in the morning, often accompanied by headache:

A restless sleep, [and] much tossing in bed and snoring will be observed. The face is usually elongated, the bones of the face are underdeveloped, as the air spaces do not have the proper circulation, the nostrils are small.

DeLong goes on to list other detrimental effects of mouth breathing, including recession of the chin and a high narrow palate with crooked teeth. Children who breathe through their mouths are observed as looking dull and expressionless and may be accused by their teachers of being inattentive in class.” — The Breathing Cure, Patrick McKeown

For children, there are many side effects of mouth breathing. We’ll get to those in more detail later. For adults, you may notice you can hear your breathing. Maybe you make a lot of noise when you eat, because you struggle to eat and breathe at the same time. You’re likely to have bad breath [6]. Mouth breathing dries the saliva, creating a breeding ground for the bacteria that cause halitosis and tooth decay. You may frequently have a blocked, stuffy, or runny nose.

When you exercise, you’re more likely to experience exercise-induced asthma, as cold, dry air hits your airways. You’ll also get colds and respiratory infections more often. Mouth breathing and a sore throat can go hand in hand, due to irritation, inflammation, and dehydration of the airway.

Long-term, you’ll have high blood pressure, greater risk of cardiovascular disease, and stress-related problems including anxiety, panic attacks and insomnia. You’ll have a lower immunity to airborne viruses, allergens and bacteria, and less resilience in the face of day-to-day challenges. Mouth breathing and anxiety creates a vicious cycle. Fast, dysfunctional breathing can make you anxious, and anxiety can cause fast hard breathing. When breathing is fast and hard, blood carbon dioxide (CO2) levels drop. People prone to panic disorder are known to have lower-than-normal levels of blood CO2 [7].

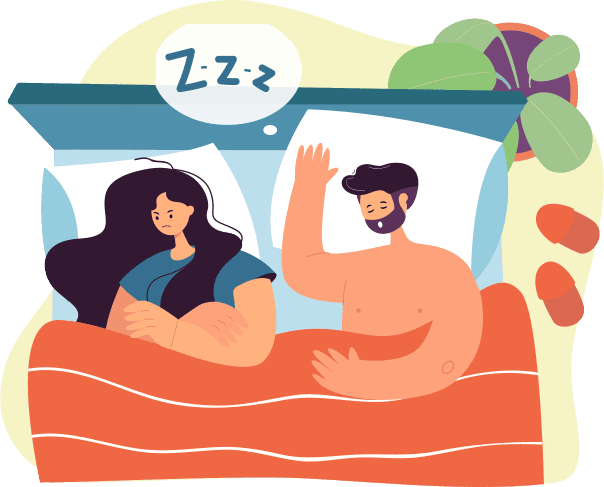

When you sleep, it’s likely you snore or even experience sleep apnea, a serious disorder in which breathing stops periodically during the night, leading to oxygen desaturation, and contributing to daytime fatigue, road traffic accidents [8] and early mortality. If you treat your sleep apnea with CPAP, mouth breathing with CPAP is the leading cause of non-compliance as air meant to support the airway leaks out through the lips [9]. You may end up needing a CPAP mask that covers your mouth and nose. This can be uncomfortable and claustrophobic.

The Effects of Mouth Breathing on the Face, Chin and Jaw

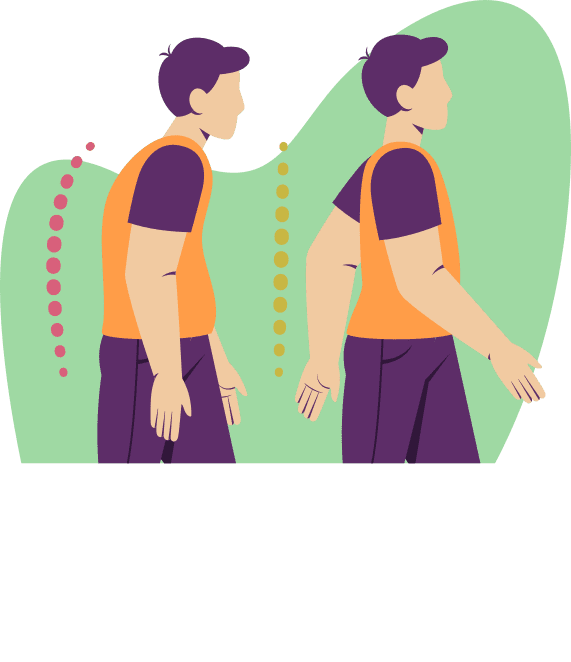

As an adult you may notice your nose is bent, the lower part of your face is elongated, your chin is recessed, and your teeth and tongue don’t seem to fit in your mouth. It’s likely your teeth are crowded and/or crooked, and you probably have heavy bags under your eyes. You may also experience neck and back pain and poor posture because you constantly push your head forward to breathe.

Does mouth breathing change your face? Over time, yes, it does. Mouth breathing has undeniable effects on the shape of the face.

How to Fix Mouth Breather Face

If you breathed through an open mouth as a child, you may need dental surgery to expand your jaw, open your airway and give your teeth the space they should have had. But before you resort to surgery, which in adulthood will be significant, it’s worth trying a gentler approach. The first step in fixing the problem is to learn to breathe through your nose. Use breathing exercises and open your nose with a nasal dilator. You can also explore myofunctional therapy, which strengthens muscles in the tongue and throat, helping to restore proper function.

Chronic mouth breathing in children can negatively affect skull and facial development and restrict the airways. If you breathed through an open mouth as a child, you may need dental surgery to expand your jaw, open your airway and give your teeth the space they need.

By age six, nearly 60% of the adult face has developed. Learning good nasal breathing early in life is essential to maximize the growth and development of the skeletal complex, the upper airway and to prevent mouth breather face. Mouth breathing in children has been attributed to genetic factors, unhealthy oral habits, and blocked nasal airways.

Blocked or obstructed nasal airways can be caused by enlarged adenoids, tonsils, and nasal concha. Risk factors include allergic rhinitis, nasal or facial deformities, or foreign bodies. (26) Other factors that can cause mouth breathing include cigarette smoking, neuromuscular disorders and congenital issues like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) and dental agenesis (missing teeth).

Does Mouth Breathing Change Your Face?

In simple terms, yes it does. For years, doctors and dentists have investigated how to fix mouth breather face. Mouth breathing causes abnormal growth that affects teeth, the face, the skull, breathing, chewing, speech and more. Mouth breather faces tend to be narrower and longer with a receding jaw and a restricted airway. The tongue is also positioned downward due to mouth breathing. (30)

Medical studies show that mouth breathing changes muscle recruitment in the upper airway. These changes alter correct growth of the face and lead to abnormal facial growth that can be easily observed.

In experiments where rhesus monkey noses were plugged to force mouth breathing, different types of skeletal, dental, and soft tissue changes occurred. Differences in the mouth included changes to the function and posture of the mandible, tongue, and upper lip. (31) At six months, the monkeys’ noses were unblocked. Normal nasal breathing returned, with improved face, teeth and skull development. (29)

Adenoids are the most common cause of upper airway blockage in children. This obstruction affects dental and facial development, causes mouth breathing and leads to “adenoid face.” (30) Nasal airway obstruction due to adenoids and/or tonsils can also cause sleep issues including mouth breathing, snoring or even severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). (27) This can lead to problems like behavioral issues and daytime sleepiness.

One study observed poorer school performance in children with enlarged adenoids. The reduced performance is thought to be due to the relationship between hypoxia (not enough oxygen) during sleep and brain function. (30)

Treatments: Can Mouth Breathing Face Be Reversed in Adults?

Most of the development of the face and skull are finished by the time we leave childhood. But before you consider surgery, which in adulthood will be significant, it’s worth trying a gentler approach to improve your breathing.

Nose Breathing

For adequate face and airway development, the ultimate goal should be permanent nose breathing. Use breathing exercises and open your nose with a nasal dilator. Addressing mouth breathing during sleep is essential.

Newborns spend nearly 80% of their time asleep. Even at six years of age, children can spend 25% of the day asleep. Nasal breathing during sleep stimulates ventilation and active reflexes which help maintain the muscles that stabilize the upper airway. (28)

Myofunctional Therapy

You can also explore myofunctional therapy, which strengthens muscles in the tongue and throat, helping to restore proper function. Myofunctional therapy has been used in muscular dystrophy to help with proper bone growth and to correct speech issues in young children. Improving the muscle function of specific airway muscles may improve the function and growth of the upper airway. (29)

Rapid Palatal Expansion (RPE)

Orthodontists perform RPE to improve obstructive sleep apnea in children. They do this by reducing airway resistance, increasing nasal volume and raising tongue posture, enlarging the airway. Rapid palatal expansion is not advisable for adults.

Alongside the improvement of obstructive sleep apnea, RPE has also been shown to modify and improve facial structure in children. In a study on the impact of rapid palatal expansion on adenoid and tonsil sizes in children; 90.0% of patients who underwent RPE had a significantly reduced adenoids and 97.5% had a reduction in tonsil size. (27)

Conclusion

Oral or mouth breathing is an important clinical symptom which may be associated with palatal growth restriction, nasal obstruction, and musculoskeletal dysfunction. (29)

Treatment of nasal obstruction in children leads to normal dentofacial development. Therefore, it is essential to address the relationship between dentofacial development and nasal airway obstruction to ensure the normal development of children. Early detection is vital to prevent mouth breathing face. (30) Muscle strengthening should also be included as an additional tool to encourage optimal craniofacial growth. (29)

Breathing Exercises for Forward Head Posture

For most people, modern life dictates that we spend many hours sitting down, often peering at a screen. It’s easy to slump and allow the head to thrust forward. All the time we’re falling forward — giving in to gravity.

When you mouth breathe, it is impossible for the tongue to rest in its proper position. Your airway becomes dry and inflamed and your nose blocks. Habitual mouth breathers push their heads forward to compensate for restricted airways. They gasp for air like fish out of water.

Over time, this forward thrust of the head causes pain and muscle fatigue. It’s hardly surprising given the average weight of the head is about 11 pounds. In fact, every inch of forward head posture increases the weight on the spine by around 10 pounds.

Mouth breathing is also self-perpetuating. It tends to be shallow — into the upper chest instead of from the diaphragm. When posture is poor, the diaphragm becomes squashed. If the diaphragm can’t move properly, you can’t breathe deeply.

The diaphragm is integral to core and spinal stabilization. It’s closely linked with balance. If it can’t move well, neither can you. And, if you don’t use your diaphragm, it will become weaker. Poor diaphragm function contributes to back pain and injury.

When the diaphragm can’t move freely, we breathe into the chest. Chest breathing is linked with activation of the fight or flight stress response. Fast, upper chest breathing also causes changes to levels of blood CO2. This changes the acidity of the blood. Combined with stress, this contributes to the formation of painful myofascial trigger points, and to muscle aches.

During chest breathing, smaller breathing muscles mobilize to help get air into the body. These include muscles in the neck called the scalenes. The scalene muscles lift the ribs during normal inhalation. But if the diaphragm isn’t doing its job, they have to work too hard. Compensatory use of the scalene muscles causes neck pain and compromises the cervical range of movement.

Take a moment to notice… Are you slumped at your desk now, or are you sitting up straight? Whatever you’re doing, try pushing your head forward and opening your mouth. Notice your breathing. Can you breathe comfortably from your diaphragm, or is your breathing forced. Can you relax your tongue in the roof of your mouth?

Now gently line up your spine so your head, heart and pelvis are balanced over each other. Close your lips and let your tongue rest in the roof of your mouth. Feel your neck relax and your mind calm. Imagine taking this quiet, poised breathing into your everyday life.

Patrick explains the role of mouth breathing in forward head posture, and why it’s important to address children’s mouth breathing early

What the Scientists Say about Mouth Breathing

Mouth breathing and forward head posture: effects on respiratory biomechanics and exercise capacity

Sabatucci, A., Raffaeli, F., Mastrovincenzo, M., Luchetta, A., Giannone, A. and Ciavarella, D., 2015. Minerva stomatologica, 64(2), pp.59-74.

“Our study confirms that oral breathing modifies head position. The significant increase of the craniocervical angles NSL/OPT and NSL/CVT in patients with this altered breathing pattern suggests an elevation of the head and a greater extension of the head compared with the cervical spine.”

What does it mean?

Breathing through the mouth causes changes to head position.

Relationship between mouth breathing and postural alterations of children

Krakauer, L.H. and Guilherme, A., 2000. The International journal of orofacial myology: official publication of the International Association of Orofacial Myology, 26, pp.13-23.

This article explores the consequences of mouth breathing vs nose breathing and examines supposed postural alterations in children within specific age groups.

The review demonstrates that children aged 8 and over, with nasal respiration, have better posture than those who continue oral breathing beyond the age of 8 years.

What does it mean?

Mouth breathing in children should be corrected as soon as possible to avoid detrimental postural changes.

Exercise capacity, respiratory mechanics, and posture in mouth breathers

Okuro RT, Morcillo AM, Sakano E, Schivinski CI, Ribeiro MÂ, Ribeiro JD. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2011 Sep-Oct;77(5):656-62..

In 2011, Brazilian researchers at Campinas State University conducted a study to assess exercise tolerance, breathing muscle strength and body posture in mouth breathing compared to nasal breathing children. Children with asthma, obesity, chronic respiratory diseases, neurological and orthopedic disorders, and cardiac conditions were excluded.

Of the 107 children, 45 were mouth breathers and 62 were nasal breathers. Examination revealed that 80% of mouth breathing and 48.4% of nasal breathing children had abnormal cervical posture and breathing pattern.

Researchers concluded that, “mouth breathing children had cervical spine postural changes and decreased respiratory muscle strength compared with nasal breathing.”

What does it mean?

Habitual mouth breathing is associated with postural changes resulting in decreased muscle strength, reduced chest expansion and impaired breathing.

Mouth breathing and forward head posture: effects on respiratory biomechanics and exercise capacity in children

J Bras Pneumol. 2011 Jul-Aug;37(4):471-9.

Scientists evaluated submaximal exercise tolerance and respiratory muscle strength in mouth breathing and nasal breathing children. A total of 92 children aged between 8 and 12 years were studied, of whom 30 were mouth breathers and 6 were nasal breathers.

The study concluded that respiratory biomechanics and exercise capacity were negatively affected by mouth breathing.

What does it mean?

Mouth breathing causes the breathing muscles (primarily the diaphragm) to become weak, so they do not work so well. When breathing is inefficient, you will become exhausted more quickly during exercise.

Assessment of the body posture of mouth-breathing children and adolescents

J Pediatr (Rio J). 2011 Jul-Aug;87(4):357-63. Epub 2011 Jul 18. Conti PB, Sakano E, Ribeiro MA, Schivinski CI, Ribeiro JD.

A study of 306 mouth breathing and 124 nasal breathing children showed that, “postural problems were significantly more common among children in the group with mouth breathing syndrome, highlighting the need for early interdisciplinary treatment of this syndrome.” In this study, researchers noted that boys are more likely to be mouth breathers than girls.

What does it mean?

Mouth breathing is present in around 50% of children, with a 60/40 split between boys and girls [6]. Children who are mouth breathers are likely to experience postural problems that can persist into adulthood.

Orientation and position of head posture, scapula, and thoracic spine in mouth-breathing children

Int J Neiva PD, Kirkwood RN, Godinho R. Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009 Feb;73(2):227-36. Epub 2008 Dec 3.

Mouth-breathing is a common clinical condition in school-age children. Some studies link this condition with poor quality of life and postural alterations.

This study investigates the orientation and position of the scapula (shoulder blade), thoracic spine (the long region of the spine between the neck and abdomen) and head posture among mouth breathing children compared with nasal breathing children.

“Mouth breathing children increased scapular superior position in comparison to nasal breathing children due probably to the position of forward head, leading to an alteration in the positioning of the mandible. The absence of significantly difference in posture pattern between groups in the present study could attributed to height-weight development in this age, as the posture of children changes in order to adapt to new body proportions, regardless of health status.”

What does it mean?

It is important to use reliable measurements when assessing postural changes in children with oral breathing routes. This will help physical therapists focus their strategies during rehabilitation.

Why do I Sleep with My Mouth Open?

Is it Bad to Sleep with Your Mouth Open?

It’s obvious that sleeping with your mouth open leads to mouth breathing during sleep. And if daytime mouth breathing is bad, nocturnal mouth breathing can be perhaps even more dangerous. Mouth breathing while sleeping leads to loud snoring, and it makes symptoms of sleep apnea much worse [11].

Sleep apnea is linked with depression, death by road traffic accident, sudden cardiac death, cardiac arrhythmias, and erectile dysfunction in men.

How to Stop Mouth Breathing While Sleeping

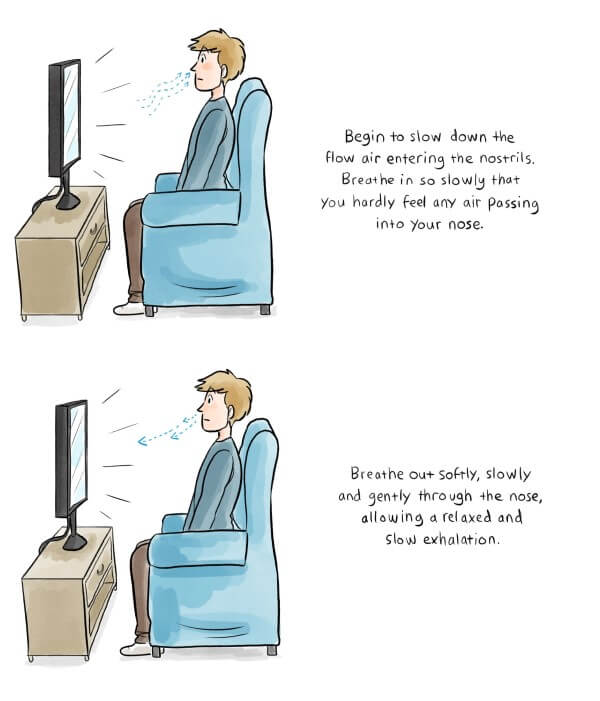

To stop mouth breathing at night, you need to stop sleeping with your mouth open. Mouth breathing is caused when the mouth falls open during sleep. To keep your mouth closed, you can practice breathing exercises that reduce the speed and flow of air you breathe. You can also try myofunctional therapy to strengthen the muscles of your tongue and throat. Some people use a chin strap, but this can cause pain in the temporomandibular joint in your jaw. If you want to keep your mouth closed while sleeping, without discomfort, use a lip tape like MYOTAPE.

To find out more about the benefits of breathing re-education for sleep apnea, read Patrick McKeown’s review in the Journal of Clinical Medicine and check out our online sleep course.

According to Dr. Christopher Winter, who is medical director of the Martha Jefferson Hospital sleep medicine center in Charlottesville, Virginia:

“There are athletes everywhere who have sleep apnea…Not only does the apnea affect their athletic performance, but it is extremely hard on their cardiovascular systems as well.”

In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing among professional football players (NFL) was reported as 14% overall, and 34% among offensive and defensive linemen [12].

Breathing through the nose in a quiet, gentle manner during sleep reduces snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. Snoring occurs due to a large volume of air passing through a narrowed space. This causes turbulence in the soft palate, nose or back of the throat.

If you snore, there are two factors at play. The first is that you are breathing too hard during sleep. The second is that your nose may be congested, causing the upper airways to become narrow.

Simply by unblocking the nose, switching to nasal breathing, and calming breathing towards normal, snoring and sleep apnea greatly reduce. Indeed, an increasing body of scientific evidence highlights the relationship between nasal obstruction, mouth breathing and snoring/sleep apnea.

Upper airway resistance is much higher when breathing is through the mouth during sleep. Obstructive apneas (holding of breath) and hypopneas (resistance to breathing) are profoundly more frequent when breathing is through the mouth [13]. And oxygen desaturation is much worse.

The good news is that sleep experts are increasingly becoming concerned about the impact of open mouth breathing during sleep. The late Dr. Christian Guilleminault of Stanford University did much to advance knowledge in this area. According to Dr Guilleminault:

“The case against mouth breathing is growing, and given its negative consequences, we feel that restoration of the nasal breathing route as early as possible is critical” [14].

At OA™ we advocate mouth taping to ensure nasal breathing during sleep. This has many benefits, as a 2020 article looking at the use of nasal nitric oxide (NO) in the fight against COVID-19 reveals:

“Our anecdotal observations also suggest that favoring nasal breathing during sleep by sealing the mouth with adhesive tape reduces common colds. This phenomenon may be due to the filtration and humidifying effects of the nose on inhaled air and to increased NO levels in the airways, which may decrease viral load during sleep and allow the immune system more time to mount an effective antiviral response” [15].

Athletes are susceptible to colds and respiratory infections including COVID. These can cause missed training days and missed competition. Yet another reason to ensure you breathe through your nose at night.

But all this leaves us with a big question — how to stop mouth breathing while sleeping?

Should I Tape my Mouth Shut at Night?

Yes. It’s the best way to ensure nasal breathing when you’re asleep. However, before you try taping, it’s important to follow some simple guidelines.

- Never tape your mouth if you feel nauseous or may vomit.

- Don’t tape your mouth at night if you’ve been drinking alcohol or taken recreational drugs.

- Only tape your mouth using a specialist lip tape, or Micropore paper tape. Never use any tape with strong adhesive, or glue not designed for the skin.

- If you are anxious about taping, try Patrick’s patented sleep tape, MYOTAPE. It goes around the mouth rather than over the mouth, so you can still open your mouth if you need to. This makes it incredibly safe.

- Always read the instructions on the packet before applying lip tape.

- If you have any concerns or a serious medical condition, consult your medical doctor before taping your mouth to sleep. The advice in these articles is not a substitute for that of a qualified doctor. If in doubt you can also find a certified breathing instructor to help.

- Always listen to your body.

How to Stop Mouth Breathing in my Child

As we’ve already seen, mouth breathing in children is a serious matter. Left unchecked, it can cause irreversible changes in facial growth and cognitive ability [16], and it contributes to behavioral disorders including ADHD [17]. In small babies, mouth breathing has been linked with sudden infant death syndrome [18].

Here are a few signs that mouth breathing may be impacting facial development for your child…

They have dental problems

Does your child have crowded teeth, dental pain, smelly breath, jaw pain, or an irregular bite? Mouth breathing causes changes in the growth of the teeth and jaws. It also causes crowding. When the tongue sits in its correct resting position (in the roof of the mouth just behind the front teeth), it helps the jaw and palate to grow wide, with nice straight teeth. During mouth breathing, the tongue cannot fulfil this function.

They constantly have a blocked nose

When a child has swollen adenoids and/or tonsils, they may resort to mouth breathing because they cannot breathe through the nose. Many parents resort to surgery to remove the adenoids or tonsils, but sometimes this is not necessary. Swollen adenoids and tonsils are aggravated during mouth breathing and may resolve when nasal breathing is restored. Equally, if your child does have surgery, it is vital to teach them to breathe through the nose after the procedure.

Removing the adenoids and tonsils can significantly reduce symptoms of sleep apnea, but one study found it only completely resolved the problem in 27% of cases [19]. This indicates there are other causative factors alongside the swollen adenoids and tonsils. Another study found that if nasal breathing is not restored, sleep apnea will recur within 3 years of surgery [20].

They have sleep-disordered breathing, snoring or sleep apnea (no child should ever snore)

“Studies have defined the risk factors of obstructive sleep apnea in children as a narrow palate, long face, enlarged tonsils and/or adenoids, and minor malocclusions (misaligned teeth), and not, as some might expect, obesity.” — The Breathing Cure, by Patrick McKeown

In his 2021 bestseller, The Breathing Cure, Oxygen Advantage founder, Patrick McKeown argues that dentists should be involved in identifying sleep-disordered breathing in children. Between 1 and 5% of children have sleep-disordered breathing, and the condition has been linked with sudden infant death syndrome [21].

They have speech changes and auditory processing disorders

Mouth breathing can cause speech disorders. If your child lisps or is slower developing speech and language than you would expect, it may be down to mouth breathing [22,23,24]. Mouth breathing can also cause a hoarse-sounding voice due to dry airways.

You may notice a difference in the shape of the jaw and chin

Children who are mouth breathers will display changes in the jaw. The face and lower jaw are likely to become longer. The child may develop an overbite and a receding chin.

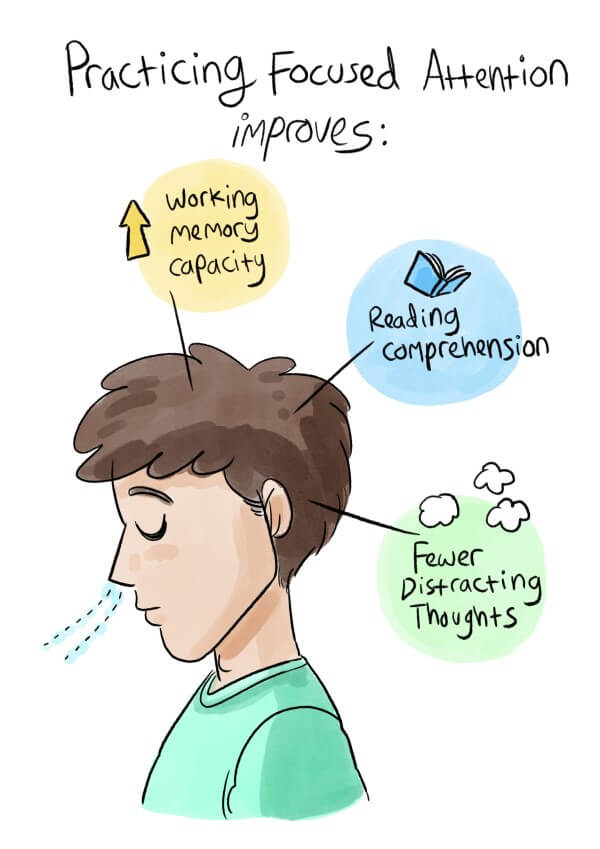

Your child may struggle to focus as school or display behavioral issues

If your child habitually breathes through his or her mouth, less oxygen will get to the brain, and sleep will be disturbed. Studies have linked mouth breathing and sleep-disordered breathing with a permanent reduction in cognitive ability, special educational needs, and ADHD.

To read more about the dangers of mouth breathing in children, visit our sister site ButeykoClinic.com.

How to Stop My Child Mouth Breathing

The good news is, Patrick’s mouth breathing tape, MYOTAPE, is available in a small size that’s ideal for children and teens. It can be worn by any child aged 4 years and older, who is able to easily remove the tape by themselves.

Treatment for mouth breathing is largely a matter of retraining the habit of nose breathing. To do this, observe when your child breathes through their mouth. Notice how they breathe when watching TV or concentrating on homework.

You can use MYOTAPE for short periods during the day as well as at night. You may like to work with a breathing instructor to help. Or try the free program of children’s breathing exercises over on the Buteyko Clinic website.

A Final Word

Breathing is fundamental to life. When it’s in balance, it supports all the body’s systems. It’s time to fix your habitual mouth breathing and give yourself the best chance of wellness.

For more information about how mouth breathing impacts sports performance, read our comparison of nose breathing vs mouth breathing.

References:

- Guilleminault, Christian, Shehlanoor Huseni, and Lauren Lo. “A frequent phenotype for paediatric sleep apnoea: short lingual frenulum.” ERJ open research 2, no. 3 (2016): 00043-2016.

- Milanesi, Jovana de Moura, Luana Cristina Berwig, Mariana Marquezan, Luiz Henrique Schuch, Anaelena Bragança de Moraes, Ana Maria Toniolo da Silva, and Eliane Castilhos Rodrigues Corrêa. “Variables associated with mouth breathing diagnosis in children based on a multidisciplinary assessment.” In CoDAS, vol. 30, no. 4. 2018.

- Palmer, Brian G. “Prevention-The Key to Treating OSA/SDB-Part II.”

- Madronio, M. R., Emily Di Somma, Rosie Stavrinou, J. P. Kirkness, Erica Goldfinch, J. R. Wheatley, and Terence C. Amis. “Older individuals have increased oro-nasal breathing during sleep.” European Respiratory Journal 24, no. 1 (2004): 71-77.

- Gargaglioni, Luciane H., Danuzia A. Marques, and Luis Gustavo A. Patrone. “Sex differences in breathing.” Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology (2019): 110543.

- Alqutami, J., W. Elger, N. Grafe, A. Hiemisch, W. Kiess, and C. Hirsch. “Dental health, halitosis and mouth breathing in 10-to-15 year old children: A potential connection.” European journal of paediatric dentistry 20, no. 4 (2019): 274.

- Meuret, Alicia E., David Rosenfield, Anke Seidel, Lavanya Bhaskara, and Stefan G. Hofmann. “Respiratory and cognitive mediators of treatment change in panic disorder: Evidence for intervention specificity.” Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 78, no. 5 (2010): 691.

- Tefft, Brian C. Prevalence of motor vehicle crashes involving drowsy drivers, United States, 2009-2013. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, 2014.

- Bachour, Adel, and Paula Maasilta. “Mouth breathing compromises adherence to nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy.” Chest126, no. 4 (2004): 1248-1254.

- Gleeson, Kevin, and Clifford W. Zwillich. “Adenosine stimulation, ventilation, and arousal from sleep.” American Review of Respiratory Disease145, no. 2_pt_1 (1992): 453-457.

- Hsu, Yen‐Bin, Ming‐Ying Lan, Yun‐Chen Huang, Ming‐Chang Kao, and Ming‐Chin Lan. “Association Between Breathing Route, Oxygen Desaturation, and Upper Airway Morphology.” The Laryngoscope(2020).

- Increased Prevalence of Sleep-Disordered Breathing among Professional Football Players. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:367-368

- Fitzpatrick MF, McLean H, Urton AM, Tan A, O’Donnell D, Driver HS. Effect of nasal or oral breathing route on upper airway resistance during sleep. Eur Respir J. 2003 Nov;22(5):827-32.

- Seo-Young Lee* , Christian Guilleminault, Hsiao-Yean Chiu,**, Shannon S. Sullivan. Mouth breathing, “nasal dis-use” and pediatric sleep-disordered-breathing. Sleep and Breathing (2015) Stanford University Sleep Medicine Division, Stanford Outpatient Medical Center, Redwood City CA

- Martel, Jan, Yun-Fei Ko, John D. Young, and David M. Ojcius. “Could nasal nitric oxide help to mitigate the severity of COVID-19?.” (2020): 168-171.

- Boyd, Andy, Jean Golding, John Macleod, Debbie A. Lawlor, Abigail Fraser, John Henderson, Lynn Molloy, Andy Ness, Susan Ring, and George Davey Smith. “Cohort profile: the ‘children of the 90s’—the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children.” International journal of epidemiology 42, no. 1 (2013): 111-127.

- Bonuck, Karen, Katherine Freeman, Ronald D. Chervin, and Linzhi Xu. “Sleep-disordered breathing in a population-based cohort: behavioral outcomes at 4 and 7 years.” Pediatrics 129, no. 4 (2012): e857-e865.

- Rambaud, Caroline, and Christian Guilleminault. “Death, nasomaxillary complex, and sleep in young children.” European journal of pediatrics 171, no. 9 (2012): 1349-1358.

- Bhattacharjee, Rakesh, Leila Kheirandish-Gozal, Karen Spruyt, Ron B. Mitchell, Jungrak Promchiarak, Narong Simakajornboon, Athanasios G. Kaditis et al. “Adenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective study.” American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 182, no. 5 (2010): 676-683.

- Lee, Seo-Young, Christian Guilleminault, Hsiao-Yean Chiu, and Shannon S. Sullivan. “Mouth breathing,“nasal disuse,” and pediatric sleep-disordered breathing.” Sleep and Breathing 19, no. 4 (2015): 1257-1264.

- Durdik, Peter, Anna Sujanska, Stanislava Suroviakova, Melania Evangelisti, Peter Banovcin, and Maria Pia Villa. “Sleep architecture in children with common phenotype of obstructive sleep apnea.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 14, no. 01 (2018): 9-14.

- de Lábio, Roberto Badra, Elaine Lara Mendes Tavares, Rafael Ceranto Alvarado, and Regina Helen Garcia Martins. “Consequences of chronic nasal obstruction on the laryngeal mucosa and voice quality of 4-to 12-year-old children.” Journal of Voice 26, no. 4 (2012): 488-492.

- Eom, Tae-Hoon, Eun-Sil Jang, Young-Hoon Kim, Seung-Yun Chung, and In-Goo Lee. “Articulation error of children with adenoid hypertrophy.” Korean journal of pediatrics 57, no. 7 (2014): 323.

- Ziliotto, Karin Neves, Maria Francisca Colella dos Santos, Valeria G. Monteiro, Márcia Pradella-Hallinan, Gustavo A. Moreira, Liliane Desgualdo Pereira, Luc LM Weckx, Reginaldo Raimundo Fujita, and Gilberto Ulson Pizarro. “Auditory processing assessment in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.” Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology 72, no. 3 (2006): 321-327.

- International Journal of Psychophysiology91, no. 3 (2014): 206-211.

- Abreu RR, Rocha RL, Lamounier JA, Francisca, Guerra M. Prevalence of mouth breathing among children. J Pediatr (Rio J) [Internet]. 2008 Oct [cited 2022 Nov 27];84(5):467–70. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/j/jped/a/hrC4mVvGdXwYgQhhpGyf3Pg/?lang=en&format=html

- Yoon A, Abdelwahab M, Bockow R, Vakili A, Lovell K, Chang I, et al. Impact of rapid palatal expansion on the size of adenoids and tonsils in children. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2022 Apr 1 [cited 2022 Nov 28]; 92:96. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC9213408/

- Chambi-Rocha A, Cabrera-Domínguez ME, Domínguez-Reyes A. Breathing mode influence on craniofacial development and head posture. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018 Mar 1;94(2):123–30.

- Guilleminault CD, Guilleminault C, Sullivan SS. Towards Restoration of Continuous Nasal Breathing as the Ultimate Treatment Goal in Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea [Internet]. Vol. 1, Enliven Archive | www.enlivenarchive.org. 2014. Available from: www.enlivenarchive.org

- Koca CF, Erdem T, Baylndlr T. The effect of adenoid hypertrophy on maxillofacial development: An objective photographic analysis. Journal of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery [Internet]. 2016 Sep 20 [cited 2022 Nov 27];45(1):1–8. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s40463-016-0161-3

- Vargervik K, Vargervik DDS, Miller AJ, Chierici G, Hat-Void E, Tomer BS. Morphologic response to changes in neuromuscular patterns experimentally induced by altered modes of respiration a.